A credit union with a capital ratio of 7% is considered to be “well capitalized.” Down to 6%, the credit union is “adequately capitalized.” Under 6%, the credit union is “undercapitalized,” and at 2% it is “critically undercapitalized.”

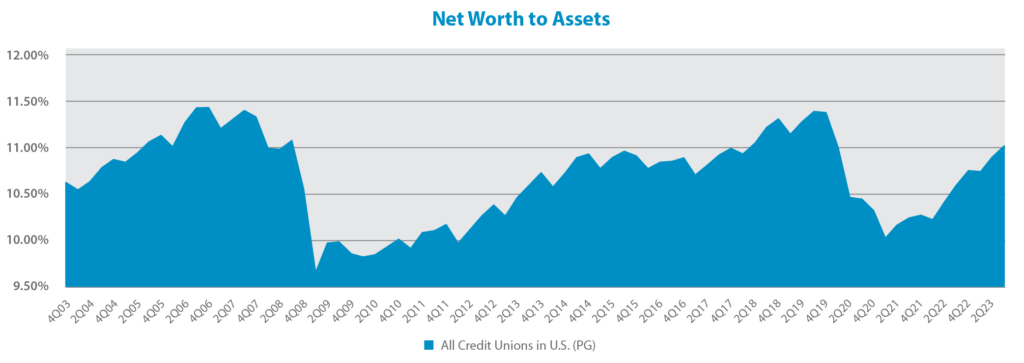

One might think, then, that credit unions maintain their capital ratios at or around 7%. However, in practice, 7% is viewed as “too low.” Consider this chart, which shows the weighted average capital ratio across the credit union industry, all the way back to 2003. As you can see, the ratio tends to creep up over time, nearly reaching 11.5%, and then drops suddenly.

This poses a few questions:

Quite simply, the industry views anything less than 7% as undesirable. Any time a credit union’s capital falls below 7%, it is subject to federal attention in the form of Prompt Corrective Action (PCA).

It’s as fun to experience as the name suggests.

While in PCA, the credit union must create and submit to NCUA a plan to increase its capital level to above 7%. The NCUA will frequently check up on the credit union to ensure it is meeting targets, and if the credit union isn’t on track, the NCUA will require further action from the credit union.

PCA is certainly unpleasant for the credit union. It feels like something you might find in a dystopian novel. “Don’t worry, this won’t hurt a bit. It’s for your own good and the good of the system.”

Truly, PCA is good for the system, but it can be painful for credit union executives, volunteers, and even sometimes members. Examiners and executives know that, at times, the ratio will drop, so they maintain a buffer between their capital ratio and the statutory 7% ratio. The 3% difference between 7% and 10%, or the 4% difference between 7% and 11%—that’s a defensive measure utilized by credit unions to prevent themselves from going into PCA when that ratio drops, as it inevitably will.

The worst part about it is that sometimes a credit union’s capital ratio may slip for reasons beyond its control. Which brings us to the second question.

Quite simply, because hard times come upon the economy—and therefore credit unions—suddenly.

The Great Recession, which credit unions did not cause, hurt credit unions tremendously. That is reflected in the reduction of the capital ratio from a high of 11.44% to a low of 9.65%. Nearly 2%.

During 2020 and 2021, when the federal government disbursed stimulus checks directly into taxpayer accounts, credit unions received much of those funds. And many taxpayers, uncertain about the future, simply sat on those funds. So, deposits at credit unions grew at record paces.

Because of the relationship between deposits and assets and the capital ratio, even though credit unions remained profitable, that profitability did not keep pace with asset growth, and capital ratios declined from a high of 11.39% to a low of 10.02%. Not quite 1.5%.

Imagine, in both scenarios, if the credit union industry were maintaining its capital ratio at a well-capitalized 7.01%. In both recent extreme conditions, the industry’s ratio would have dropped below 6%–it would have been inadequately capitalized.

Unlike at a bank, a credit union does not have the option of issuing stock to build capital in an emergency; as a not-for-profit credit cooperative, credit unions don’t have stock. The credit union must build capital slowly over time, via retained earnings. This causes credit unions to be extra-sensitive to its capital ratio.

Also note that these retained earnings are not immediately taxed, like bank retained earnings. However, they are taxed when individuals are able to benefit from them.

In the end, both credit unions and regulators know that while 7% is the statutory level, credit unions must maintain higher capital levels to avoid PCA in bad times. For this reason, examiners—the boots-on-the-ground representatives of regulators—encourage higher capital levels. Credit unions, wanting to avoid PCA in bad times, agree with the philosophy.