Utah credit unions have a broader share of the consumer deposit and loan market than their peers nationwide. Why is this?

In short, because in 1983 the commissioner of the Utah Department of Financial Institutions interpreted a state law in such a way that allowed credit unions to expand their field of membership to the entire state. Several credit unions did so, and consumers responded favorably.

In 1983, the commissioner of the Utah Department of Financial Institutions reviewed the credit union law regarding fields of membership, and allowed credit unions to expand to multiple counties.

What prompted the state commissioner to draft a rule, in 1983, to allow credit unions to expand their fields of membership to multiple counties? The following items could have played a role in her decision.

Having been given the authority by the Governor of Utah and the laws and statutes of this state, the commissioner responded to the changing economic and technological times. In a sense, she acted like a police officer in an intersection directing traffic in response to a need—and waving cars through even though the stoplight is red.

Bottom Line: in 1983, the commissioner allowed credit unions to expand beyond their prior one-county limitation.

Having approval from their regulator, several Utah credit unions began to serve broader groups of people. All the while, they maintained their not-for-profit, cooperative structure.

Utah consumers, as it turned out, responded favorably to increased access to credit unions, and began to join credit unions in increased numbers.

In 1993, the Utah Bankers Association filed suit against the DFI and thirteen credit unions that had changed their FOM charters to include multiple counties within the state—within the bounds of the rule set by the commissioner. Of these thirteen credit unions, only three had extended their membership and/or branches into a second or third county. The others had simply amended their field of membership (FOM) in anticipation of future opportunities. The UBA’s contention was that the DFI had incorrectly interpreted the law.

The lawsuit was a hypocritical brute-force attack on the success of credit unions, with the purpose of shoring up bank profits. The lawsuit was hypocritical because, for decades, banks had been poking holes in Great Depression-era legislation, pushing at the regulatory and legal bounds of what was allowed by the Glass-Steagall act.

In 1999, when the landmark Gramm-Leach-Bliley act was passed, Senator Gramm commented that, “This bill we bring to the floor of the Senate basically knocks down the barriers in American law that separate banking from insurance and banking from securities. These walls, over time, because of innovative regulators and because of the pressure of the market system, have come to look like very thin slices of Swiss cheese.”

In other words, regulators had waved banks through the red light on many occasions, to the point that the laws were ineffective. At the time, the American Bankers Association website published a gloating account of how Glass-Steagall was dismantled a piece at a time by pushing regulatory bounds.

Yet, banks were not interested in credit union regulators pushing boundaries. Of course not. It was eroding their market share and therefore their profits.

In 1998, a district court ruled in favor of the Utah bankers. Notably, the commissioner did not overstep her authority. She had acted legally and lawfully within the scope of her office—only erred in her decision.

This is not unlike a legislature that creates and passes a law that is later declared unconstitutional. Such an event does not say that the legislature broke the law. It does say that, in the eye of the judge, they erred in their judgement or interpretation of the law.

The result was an epic legislative battle between credit unions and banks that lasted from roughly 1999 to 2005. During that time, the Utah legislature, genuflecting to influential bankers and ignoring the undeniable will of a vast majority of Utahns, put state-chartered credit unions in a box that limited their ability to serve consumers.

Despite what bankers promised could not happen, a majority of credit unions assets in Utah switched to the more favorable federal charter, where it would be much harder for the Utah state legislature and banks to corral them.

By then, however, the cat was out of the bag. During the 15 years between the time the commissioner allowed credit unions to expand their fields of membership and the time the court ruled against the commissioner, Utahns had voted with their dollars. They wanted access to access to not-for-profit cooperatives.

That’s the story of why Utah’s credit unions hold a larger share of the consumer market than their peers nationally. It’s why a majority of assets in Utah credit unions are with federal institutions.

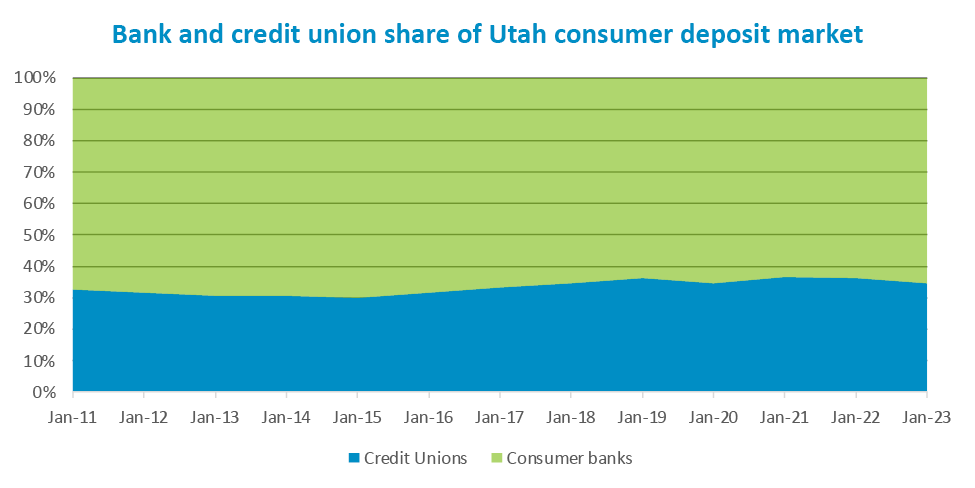

Even so, credit unions still hold a minority of consumer deposits in Utah, and will not eclipse banks any time soon.